Echoes of the past – “where the technically minded visitor discovered an outpost of an earlier cartographic culture”

Mountjoy House sits alone among the trees at the far end of Phoenix Park, four miles from Dublin city centre, along Chesterfield Avenue and down the Ordnance Survey Road, where the gas lamps that still light the road end. Deer graze close by, and in the distance, the Wicklow Mountains hang over the Dublin haze. The Ordnance Survey Office, as it was once known, is surrounded by trees said to have been planted during Queen Victoria’s visit to Dublin in 1849. It is a sublime location.

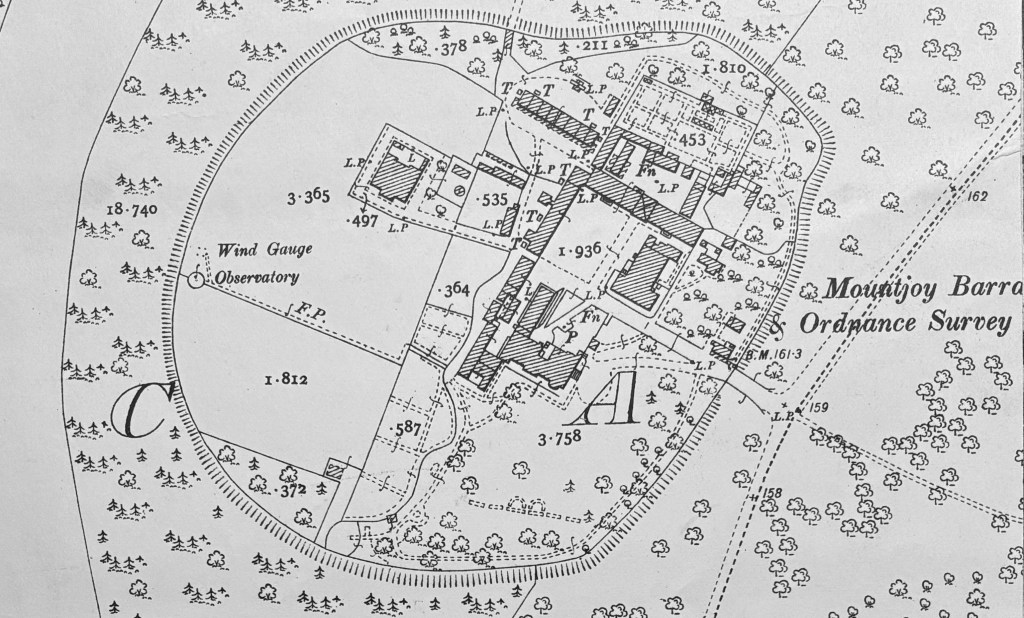

Back in 1994, I entered through the iron gates. Beyond the gatehouse was the old parade ground, now a car park. At weekends, it was empty and silent except for the imagined sound of horses’ hooves and military regalia echoing off the stone walls. Around the parade ground were the old cavalry barracks, now cartographic offices and stores. Inside the stone walls were wooden drawers stacked high full of paper maps, a paper landscape depicting Ireland in extraordinary detail, in a place “where the technically minded visitor discovered an outpost of an earlier cartographic culture”.[1] It was not hard to imagine cartographic artisans still scribing maps with quill pens in monastic calm. It was like entering a world in a different era.

As I was shown around the site, the echoes of the past still remained, still part of the institutional memory. Here stood the old print building, which once housed the printing presses, where the art of copper-plate etching and printing was practised. Here was the levelling office, where the lines were calculated and ‘closed’ by staff. Here was where the mechanical calculator was first introduced, so distrusted that the more experienced hands took home the levelling books to check the machine’s calculations by hand. Here was the duffing-out room, where cartographers huddled over light tables, painstakingly painting out errant specks of light using artists’ paintbrushes. Here, too, across the square, was the map sales office, where the public could visit and purchase paper maps – next door, the map stock room, and upstairs, the map stores, still there today, wooden shelves and drawers stacked from floor to ceiling, smelling of archived paper records.

An archway led from the central square through to the general stores and a workshop. Over the arch was a clock that set the pace for the office. It dictated the day’s schedule: a red line drawn in the attendance book after the last person to arrive on time–everyone else “red-lined” as being late; it told the time for tea, a social occasion of noise and humour; lunch-time, more socialising; and then home time, a mass exodus at 4.30 pm, likened by some as the “Charge of the Light Brigade” – the buses and trains a fifteen-minute brisk walk across the Park.

Opposite the old print room was the “red block”, where small-scale maps were mounted on linen as a special service for customers. Maps surveyed from aerial photographs were demonstrated here from the mid-1960s; here was where the Trig Office calculated the secondary and tertiary triangulations, and then further along were where the old lithographic printing machines once stood. The fire-proof store was opposite, a windowless stone building, the room above with its surprising coal fire. Just outside were two marks setting out a standard length against which the Survey’s chains were tested and, therefore, all distances in Ireland judged. A short walk from here was the canteen where Mrs O’Malley had served tea and sold cigarettes and chocolate in the 1960s, one of only two women in the Ordnance Survey. She was later replaced by Eileen, who, in turn, would be replaced by a vending machine.

The newest building sat to the rear, dated from 1974, with its more modern printing presses and stores of paper and ink, with shelves of finished maps ready for distribution and sale. An ancient printing press was still used here to produce fine prints from images etched into copper plates, a skill long lost. At the rear were the married quarters where soldiers lived, their wives no longer requiring a “certificate of character” to allow them to live on site.[2]

Some children had even been born and raised in this small military community, with Phoenix Park their playground. Fresh bread used to be delivered by horse-drawn cart by Johnston Mooney & O Brien, the smell evoking childhood memories sixty years later. [3] Milk was delivered by a man on a bike from a nearby farm in Clonsilla. He would call at the soldier’s quarters and ladle the milk from a churn strapped to the front of his bicycle into jugs held out at the door by the children for a tanner (6d). Groceries were bought from Corcoran’s, a pub and grocery at the bottom of Knockmaroon Hill. Each family had an allotment on which they grew potatoes and vegetables, and at the back, there was a walled orchard accessed through an arch, raided by children when the fruit was ripe.

Nighttime in this dark corner of the park beyond the gas lamps could be scary for young children, particularly in the dark winter months before electricity. Even the guards were nervous: one used to walk the perimeter, firing his pistol into the bushes and shouting, “Get out of there,” but he only succeeded in scaring the children and the adults, until they took his pistol away from him. On one such dark, cold winter’s night, an elderly resident’s funeral was remembered. Four black horses pulled a glass carriage with black and white feather plumage and oil lamps in each corner. The horses’ hooves clattered on the barrack square, their breath “like smoke snorted through their nostrils”. Black top-hatted and coat-tailed undertakers guided the hearse through the gates onto the square through the misty twilight, casting a cold eye around, scaring the children.

Back then, the Superintendent of the Ordnance Survey Office still lived on-site at the Big House, as the children called Mountjoy House. It was a perk of the job, extending back to Major William Reid’s arrival as the first head of the office under Colby in 1825. The Superintendents continued to live there until 1963. The house had a beautiful rose garden, well-manicured lawns, and two full-time gardeners. Turf fires heated the residence and offices, and seniority and rank dictated how close to the fire you sat.

By subscribing, you will be notified of new posts.

[1] “A Paper Landscape – The Ordnance Survey in Nineteenth-Century Ireland”, J H Andrews, Oxford At The Clarendon Press, 1975.

[2] NAI, OS/2/88/19738.

[3] “Stories from the people who put Ireland on the Map”, 2009, Finbar Dolan, p23.