Crossing the Threshold: An Ambition for Change in the Survey.

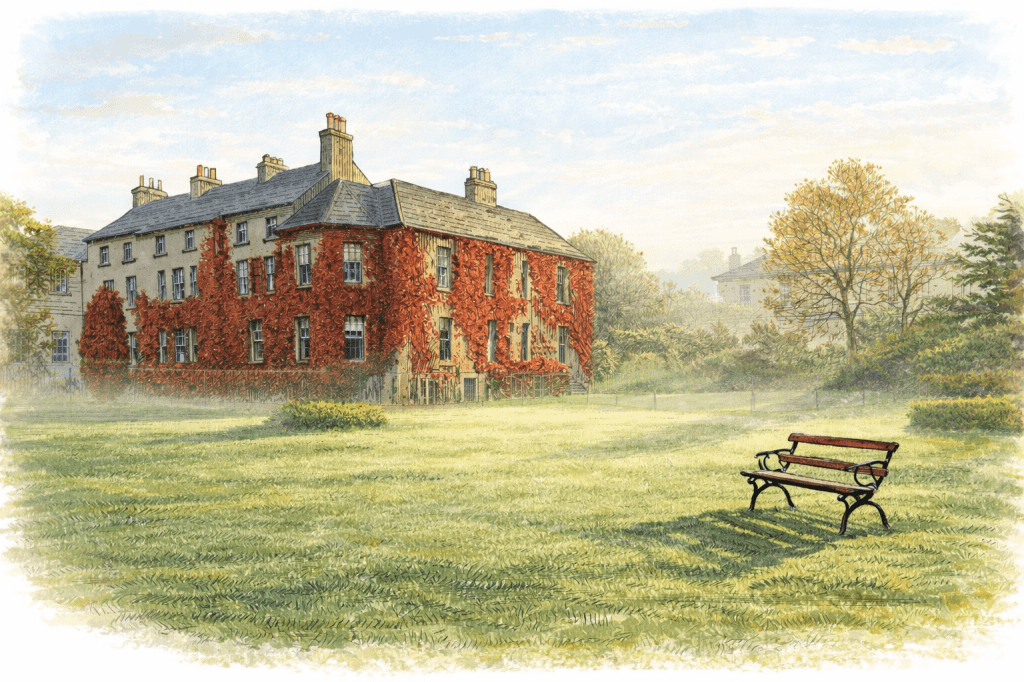

The front of the big house was covered in Virginia Creeper, a vibrant red in the early morning September sunshine. I walked through the nearly three-hundred-year-old front door in 1994, into the entrance hall, with its green carpet, creaking floorboards and white marble busts on black plinths. A white balustraded staircase swept up to the first floor, where the offices of the Archaeological Branch and the Placenames Branch were to be found. The office allocated to me was on the ground floor, to one side of the entrance hall, with a small window looking out across the old barracks. In contrast to the early Georgian architecture, it had modern office furniture, a black leather executive chair, and a computer sitting on the desk, which was not yet connected to the Internet, an innovation yet to come.

To the left of the hallway, overlooking the grounds where deer grazed among the trees, lay the offices of the two most senior officers in charge of the Survey. Their large double-fronted oak pedestal desks had green inlaid tops, and comfortable chairs set around meeting tables. Old maps and prints adorned the wood-panelled walls, which hid cupboards storing books, files, and even more old maps. I imagined the ticking of a grandfather clock.

Along a corridor was a glass hatchway and a door leading to the administration offices. It was previously a theatre built by the 1st Viscount Mountjoy, and its ornate plaster ceiling is said to be a replica of one in the old Irish Parliament building. The building creaked and groaned with age, and apart from my office, the rest of the furniture came from a different era. A musty smell prevailed throughout. A conference room to the right of the corridor was sparse, with a cupboard halfway along one wall opposite a large, forever cold, cast-iron radiator. Inside the cupboard were a few rolls of maps and an Irish Army Captain’s uniform, hanging, unused.

Shortly after my arrival, Muiris Walsh, the man in charge, called me into his office in a room now no longer used as accommodation. His Deputy, Richard (Dick) Kirwan, sat there too. It was Captain Kirwan’s unused uniform hanging in the cold, damp conference room cupboard. Neither man used his military rank, preferring a more informal approach. Nevertheless, a quiet, unobtrusive military culture pervaded the offices at Mountjoy. It was said that a staff member once introduced Muiris to the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Charles Haughey with the words, “Sir, let me introduce you to Charlie”.

Over freshly brewed coffee– a pot was always bubbling in the corner of his office– they outlined in a casual, almost offhand way, the work that was underway to establish a new map of Ireland, one that would transform the paper landscape created by Royal Engineers in the nineteenth century into a digital one suitable for the twenty-first. They were the two senior men responsible for the professional and technical oversight of an organisation of three hundred people. Muiris, close to retirement, was cautious but realistic. Dick, hungry for change, was eager to invest in the future. It was 1994, 170 years after the Survey had begun its work in Ireland. Their vision was not to reject Colby, Larcom, and Drummond’s legacy but to reinvent it for the modern, digital era.

_______________________

By subscribing, you will be notified of new posts.